Chicken Reproductive System

Anyone interested in raising chickens for eggs, whether for eating or incubation, an understanding of the female avian reproductive system is essential for recognising problems that may occur and taking action to correct them.

The avian reproductive system is designed to accommodate the risks associated with being a bird. Other than birds of prey eg hawks, most birds are prey. Being close to the bottom of the food chain, birds require unique strategies for reproducing that also allow them to retain the ability to fly. Birds do this by producing offspring that develop outside of their body aka the “egg”. All the nutrients needed for an embryo to fully develop are provided in the egg before it is laid. It is for this reason that eggs are so nutritious, however, puts offspring at higher risk of nutrition related disorders.

Poultry lay eggs in clutches after which they go broody or they carry on and repeat the laying cycle after a break of a day or so. Clutch size varies from bird to bird and typically in the wild consists of 4-8 eggs which are then brooded. Human selection however has affected this greatly to the point that some birds carry on laying and never go broody whilst others have been selected for broodiness and will go broody despite laying few to no eggs and can be set off simply by the sight of a golf ball in the nest box!

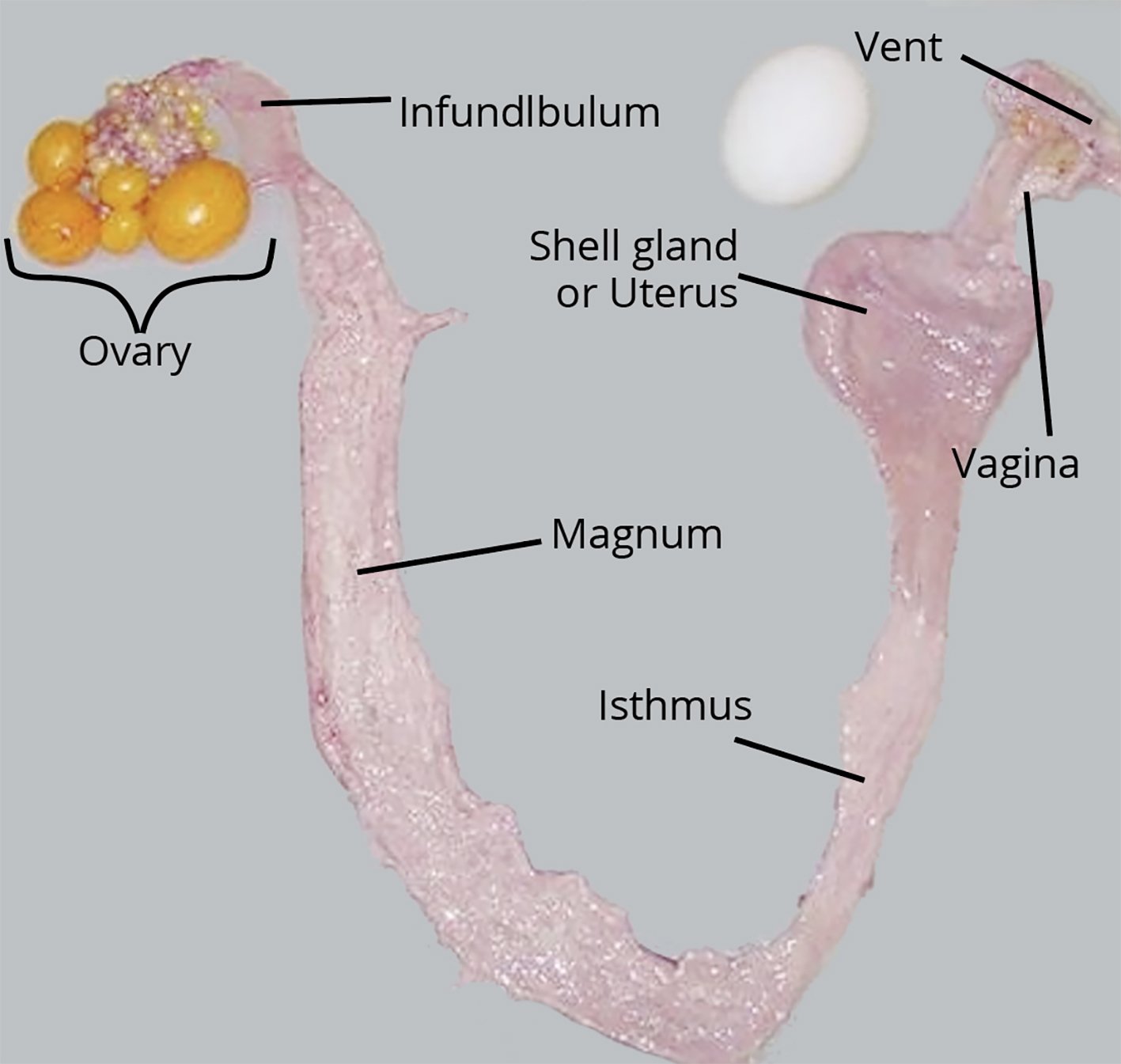

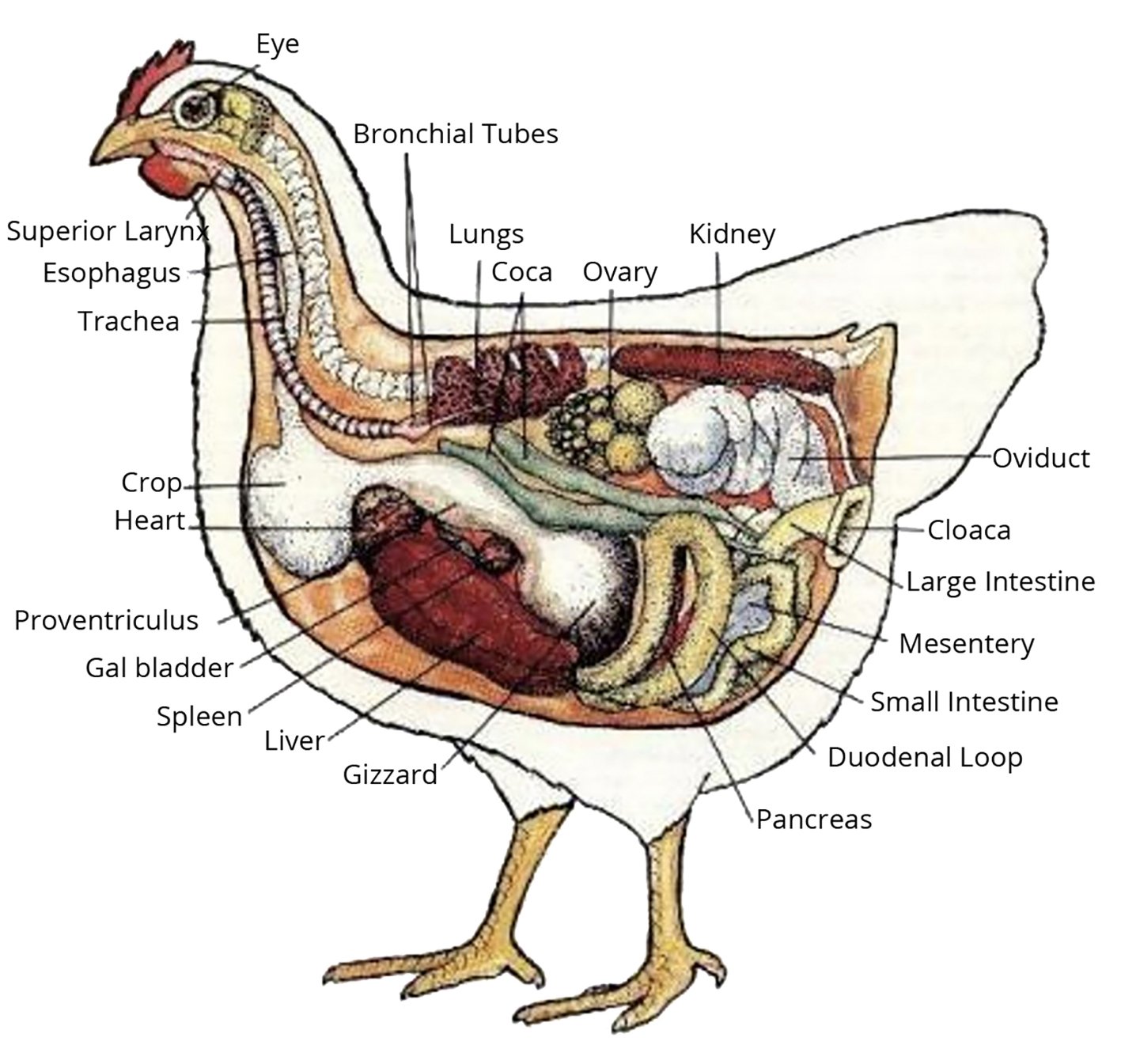

The reproductive system of a hen is made up of two parts: the ovary and the oviduct. Ova (yolks) develop in the ovary. When an ovum (one yolk) has matured, it is released from the ovary into the oviduct and is termed ovulation.

In the oviduct, glands secrete substances that form other parts of the egg, such as the albumen (egg white) and the shell. The time for a hen to transform a yolk into a fully developed egg and lay that egg is about 25 to 26 hours. Typically, about 30 to 75 minutes after a hen lays an egg, the ovary releases the next ovum/yolk.

However, the female chicken reproductive system is sensitive to light exposure, especially the number of hours of light in a day. In chickens, ovulation usually occurs under normal daylight conditions and almost never after 3:00pm. So, when a hen lays an egg too late in the day, the next ovulation occurs the following day, and the hen has a “day off”.

In times of the year where day length hours are shorter the chance of this delayed ovulation are greater and why egg laying is often more sporadic. Selective breeding has counteracted this to some degree especially in commercial strains so many of these birds will lay well throughout winter. In commercial operations the housing sheds have timed lighting regimes to maximise egg output. This can be put to use by backyard breeders also to increase laying efficiency.

Parts of the female chicken reproductive system

The reproductive system is made up of the ovary and the oviduct. (See Fig 1 and Fig 2) In almost all species of birds, including poultry, only the left ovary and oviduct are functional. Although the female embryo has two ovaries, only the left one develops. The right one typically regresses during development and is non-functional in the adult bird. (There have been cases in which the left ovary has been damaged and the right one has developed to replace it.)

There are cases of birds developing with both sets of reproductive organs also, these are often Chimeras (individuals containing two sets of genetic material, often due to absorption of a twin) and will express features of both sexes to varying degrees. Ones that successfully lay eggs can produce viable offspring.

Fig 1. Reproductive tract of a female chicken. Source: Jacquie Jacob, University of Kentucky.

Fig. 2. Location of the reproductive tract in a female chicken. Source: Public domain

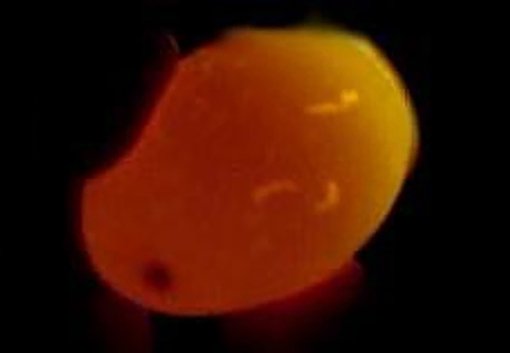

Fig 3. Ovary of a chicken in egg production. Source: Jacquie Jacob, University of Kentucky

OVARY

The ovary (Fig 3.) is a cluster of developing ova, and is located under the birds synsacrum or fused pelvis and spine. The ovary is fully formed when a chick hatches but is very small until the chick reaches sexual maturity. At hatch, a pullet chick has tens of thousands of ova, or potential eggs that theoretically could be laid, although most never develop to the point of ovulation. The maximum number of eggs a hen can lay in her life time is determined when she hatches because no new ova form after this.

Each ovum starts as a single cell surrounded by a vitelline membrane. As the ovum develops, yolk is added. The colour of the yolk comes from fat-soluble pigments, called xanthophylls, which are obtained from the diet. Hens fed diets with white maize, sorghum, millet, or wheat typically produce eggs with pale yolks. The colour of yolks can be improved by ensuring access to grass or the addition of marigold petals or yellow maize to feed. The ovum is enclosed in a sac that ruptures along the stigma, or suture line, during ovulation.

OVIDUCT

When ovulation occurs, the ovum (yolk) enters the oviduct. A mature oviduct is a twisted tube that if stretched out is just over two feet long and is divided into five major sections. These sections are the infundibulum, magnum, isthmus, shell gland, and vagina.

The first part of the oviduct, the infundibulum is 7-10cm long and engulfs the ovum released from the ovary. The released yolk stays in place, and the muscular infundibulum moves to surround it. The yolk remains in the infundibulum for 15 to 17 minutes. Fertilization, if it is going to occur, takes place in the infundibulum.

The next section is the magnum. At 30cm long, it is the largest section of the oviduct, (magnum being the Latin word for “large”). The yolk remains here for 3 hours whilst albumin is added around the yolk.

The third section is the isthmus, which is 10cm long. The isthmus is where the inner and outer shell membranes form. The developing egg remains here for 75 minutes.

The next secttion of the oviduct is the shell gland (or uterus), which is 10-13cm long. In this section, the shell forms on the egg. The shell consists mainly of calcium carbonate. On average about 8-10% of the total calcium present in a hens body is mobilized from the bones to make the egg shells. This bone calcium provides 47% of the calcium required to make a shell, and the hen’s diet provides the rest. Pigment deposition, if there is any, occurs in the shell gland. The egg remains here for 20 or more hours.

The last part of the oviduct is the vagina, which is about 10-12cm long. The vagina does not really play a part in egg formation but is important in the laying of the egg. The vagina is made of muscle that helps push the egg out of the hen’s body. The bloom, or cuticle, forms on the egg in the vagina prior to laying. The egg travels through the oviduct small end first but turns in the vagina and comes out large end first.

Near the junction of the shell gland and the vagina are deep glands known as sperm host glands that can store sperm for long periods of time, typically 10 days to 2 weeks however there are anecdotal reports of as long as 4-5 weeks! When a hen lays an egg, sperm can be squeezed out of these glands into the oviduct and then can migrate to the infundibulum to fertilize a newly released ovum.

Egg irregularities

Various events can occur during reproduction that cause irregularities in eggs. Some of these irregularities affect the quality of the egg or consumer acceptance of the egg.

MOTTLING

If the vitelline membrane surrounding the yolk becomes damaged, pale spots or blotches develop on the yolk. Although the appearance of the yolk has changed, there is no effect on the egg’s nutritional value. Feeds that contains gossypol or tannin eg sorghum can increase the incidence of mottling. A calcium-deficient diet also has this effect.

DOUBLE YOLKERS

This phenomenon can be related to hen age, but genetic factors also are involved. Young hens sometimes release two yolks from the ovary in quick succession. Double-yolked eggs are typically larger in size than single-yolked eggs. Double-yolked eggs are not suitable for hatching as they typically have inadequate nutrients and space available for two chicks to fully develop and hatch. It has happened, but is rare.

YOLK-LESS EGGS

(Sometimes referred to as pullet eggs) are usually formed when a bit of tissue is sloughed off the ovary or oviduct. The tissue stimulates the secreting glands of the different parts of the oviduct, and a yolk-less egg results.

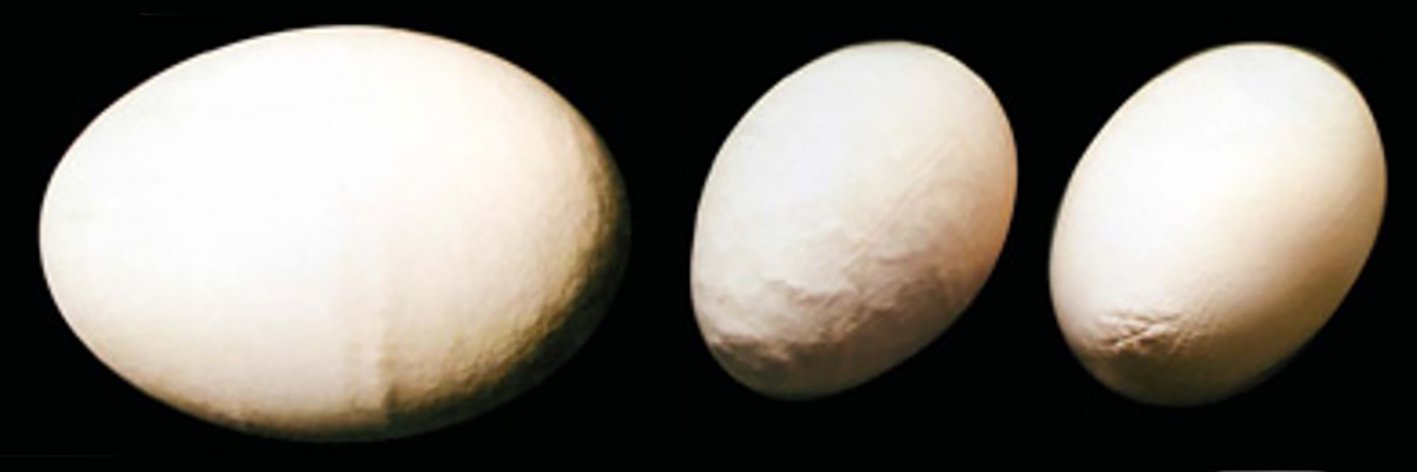

EGG WITHIN AN EGG

This occurs when an egg nearly ready to be laid reverses direction, moves up the oviduct, and encounters another egg in the process of forming. A new layer of albumen, new membranes, and a new shell form around the first egg, resulting in an egg inside an egg. No one knows exactly why they happen

SHELL LESS EGGS

Occasionally, a hen lays an egg without a shell that looks like a water balloon if found whole. The shell membranes form around the yolk and egg white, but the egg bypasses the shell-forming stage, and the shell is not completely deposited. There is no need to be concerned if it only happens sporadically. If it occurs frequently or consistently however there may be an infection in the oviduct affecting the shelling gland or a nutrition problem, primarily a deficiency of calcium, phosphorus, and/or vitamin D, may exist. Infectious bronchitis and egg drop virus have been known culprits for shell-less eggs. They are generally transient infections but long term damage to the shelling gland can occur in some cases.

BLOOD SPOTS / MEAT SPOTS

Blood spots are normally found on or around the yolk. The main cause of a blood spot is a small break in one of the tiny blood vessels around the yolk that occurs when the yolk is ovulated. High levels of hen activity during the time of ovulation can increase the incidence of blood spots.

Meat spots are usually brown in colour and are more often associated with the egg white. They form when small pieces of the wall of the oviduct are sloughed off while the developing egg is passing through.The incidence of blood spots can be higher in brown-shelled eggs, and are harder to identify via candling.

In commercial operations, eggs with blood spots and meat spots typically are identified during candling and removed.

Source: Jacquie Jacob, University of Kentucky.

SHELL ABNORMALITIES

Problems can occur when an egg’s shell is developing. The most obvious relate to shell texture. Occasionally, the shell becomes damaged while the egg is in the shell gland and is repaired before the hen lays the egg. This repair results in a thickened area known as a body check.

Occasionally, thin spots in the shell or ridges form. These shells are weaker than those of normal eggs, so eggs with thin spots are removed during inspection of table eggs and should not be used as hatching eggs.

ABNORMAL SHAPES

Can be due to issues with the muscles in the oviduct contracting at the wrong time. Ideally avoided for hatching as they often prevent the chick from attaining the correct position for hatching.

POROUS EGGS

These eggs are often formed when there is insufficient Calcium available or when the shelling gland is recovering from an infectious insult. These eggs often fail if incubated and can be prone to breaking if put under a broody to hatch and are ideally avoided.

REPRODUCTIVE ISSUES

There are a number of common reproductive problems/issues potentially encountered, and ways of treating or managing them. Some treatments can be conducted at home, but others require the involvement of a vet.

Please always put the welfare of your bird first, if you’re not confident performing any of the following suggestions please seek professional advice.

Rooster Infertility

This is generally due to one of four main reasons:

Lack of sperm

Lack of viable sperm

Lack of energy to copulate

Lack of physical access or poor mating technique

Causes can include:

Lack of physical access relates mainly to the excessively fluffy breeds. The amount of fluff around the vent gets in the way of the “cloacal kiss” and is remedied by trimming or removal (plucking) of feathers around the vent in both sexes.

Vent feathers clogged with faeces or louse eggs will also prevent access by the male bird as well as make him too irritated to mate.

Heavy parasite burdens will reduce the birds vigour and any concurrent disease like mycoplasma can render a male infertile so good parasite control and nutrition of your birds prior to mating season is of vital importance to supporting good fertility in your males.

Consider social factors, such as multiple males in the pen as they may compete with each other and push each other off the hens preventing successful copulation.

Artificial insemination is possible in chickens and requires very little to perform. There are several YouTube videos demonstrating techniques, this can be a useful tool in males with poor breeding technique or physical features that make mating more difficult.

Stressors is a large topic. Check out the Poultry NZ newsletters available free to download from their website, there is an article on stressors, it’s well worth reading.

Female reproductive problems

Lash egg

OVIDUCT INFECTIONS / SALPINGITIS

These are normally only picked up when a bird produces what’s known as a lash egg. This is effectively pus (sometimes they’ll include shed oviduct lining or clotted blood also) and due to being in the egg tract often looks like a malformed egg at first glance until picked up. The most common cause is an E coli infection that has managed to ascend into the oviduct from the intestinal tract/cloaca. This can be a route for infection of the air sacs and secondary respiratory issues.

The main form of treatment for salpingitis is an antibiotic course however in some cases the birds can effectively clear the infection on its own given supportive treatment. If the bird is bright and eating you can trial keeping inside in a warm area with a vitamin supplement to help boost the immune system however if the bird is becoming inappetent or depressed/lethargic it is best seen so an antibiotic course can be dispensed. Despite antibiotic treatment permanent damage can still occur to the egg tract and cause future issues with laying or egg shell quality.

Penguin stance

EGG PERITONITIS

This problem occurs when a hen starts ovulating eggs into the abdominal cavity instead of the egg tract. The yolks build up and eventually cause issues either by becoming secondarily infected with bacteria or by taking up too much room in the abdomen making it difficult for the bird to breath. This is more common in the commercial breeds due to their high ovulation rate and the abdomen can become quite full within a couple of weeks.

Signs of this include altered walking, often described as waddling or a penguin stance, a full swollen abdomen often covered in faeces due to increased water intake and panting or breathing issues and anorexia.

Egg peritonitis can occur secondary to, or in conjunction with salpingitis and needs a veterinary consult to fix. They will carefully remove the yolk build up from the abdomen with a large needle, if any bacteria are present a course of antibiotics are required. However the important part of treatment involves stopping further yolks being ovulated. In commercial breeds this can be done by placing a hormone implant into the muscle called Suprelorin, which halts ovulation for anything from 2-9 months. The implant normally costs around $150-200 plus the anaesthetic fee (it needs to be implanted into the breast muscle which is a painful procedure awake).

Putting on a low protein diet plus low light regime can be trialed and may be more effective for the heritage breeds however regular visits are needed to keep pulling out any yolk material until it stops accumulating. Birds given the implant therapy sometimes resume normal ovulation into the egg tract and carry on with normal laying. However if the bird originally got egg peritonitis due to scarring or injury to the egg tract then they will most likely ovulate back into the abdomen once the implants effects wear off.

VENT GLEET

This condition is the common name for cloacitis or inflammation of the cloacal area. It’s most commonly attributed to a yeast infection however can actually be secondary to a variety of causes.

The feathers around the back are usually covered in faecal material and the underlying skin is red and inflamed. The bird’s abdomen may be bloated, and they may have diarrhoea. In severe cases there can be ulceration of the skin/cloaca and formation of a diptheric membrane and the bird will likely be quite depressed by this point.

The most effective management for this condition depends on correct identification of the cause. If it’s due to a yeast overgrowth, antibiotics are more likely going to make it worse. Its recommended you get a poo sample assessed under a microscope as yeast organisms are easy to spot. You can also check for other parasites such as worms and coccidiosis at the same time which can also predispose to this condition.

If yeast is not involved and the skin is not ulcerated, then management with topical antiseptic washes such as chlorhexidine can get a mild case under control.

If the poo sample is full of yeast organisms, it may be related to the birds diet, with regular feeding of bread a common culprit. In some cases, removing the bread from the diet and applying an antifungal cream to the inflamed skin is adequate, but if the bird continues to produce lots of chalky white faeces, they may need an oral antifungal course to get it under control. If seeing a vet for this is not an option try adding some pro biotic yoghurt or capsules into the bird’s diet, this may be enough.

Birds that constantly have this issue on and off unfortunately have the lesser known cause of vent gleet which is due to a herpes virus. These viruses, once contracted remain with the bird for life and tend to flare up with any form of stress. The fungal and bacterial forms of vent gleet are not generally contagious HOWEVER the viral form is.

IMPORTANT: if you have a bird that is constantly getting repeat bouts of this, the recommendation is to cull from the flock in the interests of the rest of your flock’s health, as well as the birds welfare, as the inflammation and secondary infection is painful.

PROLAPSE

Often secondary to the laying of a large egg, sometimes the oviduct or intestine gets partially pulled out with the egg or can protrude if the hen strains excessively. Treatment of this comes down to timely identification as left too long, these birds often become victims of vent pecking/cannibalism, as chickens are highly attracted to red and can seriously damage the tissue leading to shock and septicaemia.

If found wash the area with warm saline to moisten the tissue, and with a gloved lubricated finger gently replace it back in. Haemorrhoid crème can be applied prior to replacement to help reduce the swelling and prevent it re prolapsing. If the tissue looks damaged or keeps prolapsing it is best to contact your vet for antibiotics and anti-inflammatories. Occasionally a stitch or two is needed to keep it in.

If the prolapse occurred secondary to a large egg there is a high chance of recurrence so reducing the protein content of the diet and keeping in a lower light level environment can be trialed to reduce egg size and frequency of laying. If the bird is straining due to worm burden or diarrhoea this needs to be addressed to prevent re-occurrence

EGG BINDING

Egg binding is the condition where an egg gets stuck in the oviduct (normally the shelling gland) or the entrance to the cloaca.

There can be a number of causes that can increase the risk of this happening. It’s important to realise this is a medical emergency and needs to be correctly identified as the problem and appropriately managed to have a good outcome for the bird.

Please refer to our separate article regarding Egg Binding, find it HERE.

In summary

The conditions and treatments recommended in this article are aimed at family pet situations.

Unfortunately, if you are a breeder, or have the birds purely to supply lots of eggs, your best course of action is to have the bird humanely euthanised. For a breeder the condition could be heritable or contagious and cause future flock problems.

For the person wanting eggs most of these condition/treatments even if successful result in reduced or zero egg production or the bird is prone to future episodes.